Thank you so much Janet, Jul, Marilyn, Delphine, Monique, Dieuwke, Karin, Elizabeth, Marga, Lisa, Anna, Eva, Marlène, Sophia, Charlotte, Deirdre, Rita, Amanda, Penny, Danielle, Anna, Simone, Eva, Louise, Tara, Maryan, Sophie, Megu, Yoko & Lucy for giving your cooperation to the new PreWarCar-PostWarClassic snaphot Calendar. We will give last minute preparations to the pre print proces and then the calendars will go out to all who are depicted in the calendar. Some 36 girls and ladies will be included, as every single month has no less than 4 photos, one large, three a bit smaller. As an example here’s a preview of May. And here’s the cover. The calendar will be a bit larger than last year. 31 cm wide and 44 cm high. Ordering details to follow early next week.

Autor: omdecultură

-

Habsbourg, une dynastie au cœur des racines de l’Europe

La passion de Jean des Cars pour les grandes dynasties européennes, notamment pour celle des Habsbourg, ne se dément pas. Auteur de deux ouvrages sur Sissi, le journaliste, qui n’en finit pas de transmettre son goût de l’histoire au plus grand nombre, signe cette fois-ci une somme, à la fois vivante et fouillée, qui retrace, sur sept siècles, La Saga des Habsbourg. L’occasion d’un voyage au cœur des racines de l’Europe.

Cette aventure familiale, incroyablement romanesque, débute avec Rodolphe de Habsbourg. En 1273, alors qu’il a cinquante-cinq ans, ce représentant d’une famille noble peu fortunée, originaire d’Alsace, est élu par «les sept princes allemands électeurs», sur proposition du pape Grégoire X. Rodolphe Ier prend ensuite la tête du Saint Empire romain germanique qui, précise l’auteur, «n’est pas une monarchie absolue mais une sorte de contrat associatif pour régler la vie commune dont le maître a le pas sur tous les autres souverains européens».

Choisi parce qu’on le pensait facilement manipulable, et qu’il fallait en finir avec une période d’anarchie qui avait duré un quart de siècle, Rodolphe se révéla être un souverain de grande envergure. À tel point que sa famille régnera jusqu’à ce que, le 11 novembre 1918, Charles de Habsbourg-Lorraine renonce à exercer le pouvoir en qualité d’empereur d’Autriche.

De Charles Quint à Sissi

Au fil des siècles, l’empreinte des Habsbourg ne cessera pas de marquer l’histoire de l’Europe. Parmi les figures de cette dynastie hors norme, Charles Quint est bien sûr mythique. Ce qui n’empêche pas Jean des Cars d’évoquer le physique ingrat du rival de François Ier. Ainsi, en observant les tableaux de Bernard Van Orley, il évoque la «mâchoire prognathe » du souverain et sa «bouche perpétuellement ouverte ». Une particularité qui fit dire à Charles Quint lui-même, non sans humour, que «ce n’est pas pour mordre les gens». Mais cela n’a certainement pas suffi à rassurer le roi de France…

Les conflits entre les Habsbourg et la France furent récurrents. Ainsi, la courageuse Marie-Thérèse, archiduchesse d’Autriche âgée de vingt-trois ans à la mort de son père, l’empereur Charles VI, dut faire face à une coalition anti-Habsbourg menée par le roi de Prusse Frédéric II allié à Louis XV. De plus, Marie-Thérèse, en tant que mère de Marie-Antoinette, fut accusée, non sans raison, de faire pression sur sa fille, devenue reine de France, afin qu’elle favorise les intérêts autrichiens.

Puis vint la tornade napoléonienne. Elle provoqua la fin du Saint Empire, alors dirigé par François II. Le souverain devint alors François Ier d’Autriche, monarque d’un seul État. Quant à l’incroyable mariage de Napoléon avec Marie-Louise, fille de l’empereur François, il n’empêchera finalement pas une coalition entre l’Autriche et la Prusse, contre la France.

Décidément indestructible, la dynastie des Habsbourg s’illustre encore brillamment avec l’empereur François-Joseph et sa séduisante femme Sissi. Puis, même après la renonciation de Charles Ier en 1918, un souverain assoiffé de paix, le prestige et l’autorité morale de cette famille perdureront. Ainsi Otto, prince héritier né en 1912, sera un farouche opposant à Hitler.

La saga des Habsbourg de Jean des Cars Perrin, 504 p., 22,90 €.

-

Irène Frain : Les mille et un contes bretons

Une schéhérazade bretonne, voilà comment on devrait qualifier Irène Frain. Avec ces vingt-huit contes où il est question d’Armorique, d’océan, de marins, de rêves et d’attente, la romancière offre de superbes moments de lecture. Par la magie du verbe, on replonge en enfance, même si ces textes ne s’adressent pas aux enfants. Bien au contraire, car il est aussi question de chimères, de drames et de morts. Après tout, les contes des Mille et une nuits s’adressent-ils aux plus petits? Ceux écrits par l’historienne Irène Frain ont été découverts par le plus grand des hasards à la Bibliothèque nationale de France il y a plus de trente ans. «Les pages de ces fascicules reliés d’un simple fil étaient souvent en lambeaux; et la couverture était un carton si fragile qu’elle se cassait entre les doigts quand on la manipulait» , souligne-t-elle dans un avant-propos qui est à lui seul un conte fascinant.

Native de «L’Orient»

Vivant entourée de narratrices, conteuse elle-même, Irène Frain, native de Lorient (on disait alors L’Orient) a décidé de mettre son grain de sel et de redonner une nouvelle vie à ces récits, elle les a adaptés, par une écriture plus vive, plus personnelle, avec des rythmes plus soutenus – c’est sa façon de transmettre cet extraordinaire héritage breton. Le conte qui donne le titre au recueil – Le Navire de l’homme triste – symbolise l’ensemble: il est complètement breton et absolument universel. Un capitaine au long cours cherche à tout prix un bateau à commander, il rencontre le diable qui lui propose un navire en échange de son âme. Heureux de ce pacte, le capitaine croit escroquer le diable avec une fausse signature…

Il y en a des plus doux – quoique, à la réflexion… – avec ce texte qui ouvre le recueil : Conte du sel et de la Lune. Vous ne le saviez certainement pas, mais, avant, il y a bien longtemps, l’océan avait un goût de miel, on pouvait même y boire comme à l’eau des fontaines… Mais il y eut une femme d’une beauté à tomber par terre – et ils sont nombreux à être tombés par terre: un capitaine, un seigneur… Et il y eut aussi la Lune, qui était maîtresse de l’océan… à la lecture, on saura pourquoi la mer à un goût de sel.

Irène Frain a consacré son dernier texte à la réalité derrière le conte, une sorte de décryptage des légendes. Mais le mystère et la magie demeurent.

Le Navire de l’homme triste et autres contes d’Irène Frain, L’Archipel, 360 pages, 19,95 €.

-

Panouri decorative in stil neoromanesc

Unul dintre cele mai vizibile si impresionante elemente ale stilului arhitectural neoromanesc sunt panourile decorative care pun in evidenta zone ale fatadei sau scarilor de acces a cladirilor. Acestea contin o bogatie de design-uri axate pe un numar de motive inspirate din panoplia decorativa a bisericilor medievale tarzii din Valahia, cum ar fi motivul paunilor in Gradina Domnului, vulturul protector sau leul pazind Portile Raiului. Sunt de asemenea cazuri in care panourile decorative contin reprezentari abstracte de motive nereligioase intr-o varietate de design-uri. Mai jos sunt cateva exemple din bogatia de asemenea atractive artefacte arhitecturale care impodobesc case in stil neoromanesc din Bucuresti si Targoviste.

Panoul de mai sus este o reprezentare a vulturului protector, simbolul binelui, pazind Gradina Domnului, cuprins intr-o batalie maniheica cu un sarpe, metafora raului. Gradina Domnului este imaginata ca o vita de vie luxurianta, plina de struguri, ale carei vrejuri se contorioneaza in forma unei cruci grecesti in jurul vulturului, o aluzie a faptului ca divinitatea suprema vegheaza aceasta batalie fara de sfarsit intre bine si rau.

Panoul din a doua fotografie este redat mai schematic, aerisit; o indicatie a influentei stilului Art Deco asupra neoromanescului, care a inceput sa se manifeste de prin prima parte a anilor 1930.

Panou decorativ neoromanesc, functionand ca gura de ventilatie pentru pod, casa de la sfarsitul anilor 1920, Targoviste. (©Valentin Mandache)

Fotografia de mai sus arata o folosire imaginativa in scopuri decorative a gurii de aerisire a unui pod de casa, redata in forma unei cruci grecesti abstracte, acoperita de un gratar de fier forjat continand la randul lui cruci de acel tip.

Panou decorativ in stil neoromanesc, casa de la mijlocul anilor 1930, Targoviste. (©Valentin Mandache)

Acest al patrulea panou decorativ contine un interesant motiv floral care nu are trimiteri religioase imediate, redat intr-o maniera mai schematica, in categoria celui de al doilea exemplu, rezultatul importantei influente a stilului Art Deco pe scena arhitecturala romaneasca din anii 1930.

***********************************************

Prin aceasta serie de articole zilnice intentionez sa inspir in randul publicului aprecierea valorii si importantei caselor de epoca din Romania – un capitol fascinant din patrimoniul arhitectural european si o componenta vitala, deseori ignorata, a identitatii comunitatilor din tara.***********************************************

Daca intentionati sa cumparati o proprietate de epoca sau sa incepeti un proiect de renovare, m-as bucura sa va pot oferi consultanta in localizarea proprietatii, efectuarea unor investigatii de specialitate pentru casele istorice, coordonarea unui proiect de renovare sau restaurare etc. Pentru eventuale discutii legate de proiectul dvs., va invit sa ma contactati prin intermediul datelor din pagina mea de Contact, din acest blog.

-

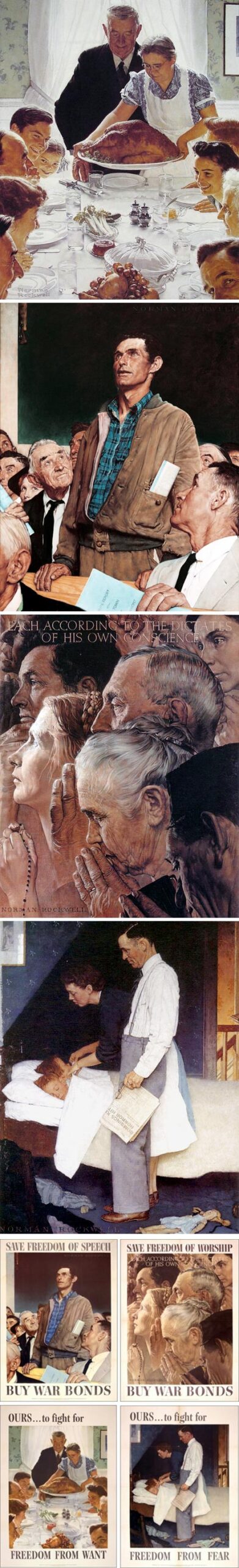

Rockwell’s four freedoms

Most Americans associate Norman Rockwell’s iconic painting of the formal family meal, shown above, top, with today’s holiday of Thanksgiving, and its traditional signature main course of roast turkey.

The painting, however, was painted with a different intention (even though the model for the turkey was actually the turkey from his own family Thanksgiving dinner).

Titled Freedom From Want, the painting was originally part of a series of four; I’ve pulled the top one out of it’s usual third position in the sequence here. The others were Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship and Freedom From Fear.

They were Rockwell’s response to a speech delivered by then President Franklin D. Roosevelt to Congress in January of 1941, in which he spoke of four essential freedoms that should be recognized and guaranteed everywhere in the world:

“In the future days, which we seek to make secure, we look forward to a world founded upon four essential human freedoms.

The first is freedom of speech and expression — everywhere in the world.

The second is freedom of every person to worship God in his own way — everywhere in the world.

The third is freedom from want — which, translated into universal terms, means economic understandings which will secure to every nation a healthy peacetime life for its inhabitants-everywhere in the world.

The fourth is freedom from fear — which, translated into world terms, means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a point and in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in a position to commit an act of physical aggression against any neighbor — anywhere in the world.

That is no vision of a distant millennium. It is a definite basis for a kind of world attainable in our own time and generation. That kind of world is the very antithesis of the so-called new order of tyranny which the dictators seek to create with the crash of a bomb.”

The speech was meant to prepare Congress, and the American public, for Roosevelt’s intention that the country should become directly involved in opposing Nazi Germany in its widening military domination of Western Europe, which the U.S. did, with a declaration of war (such an old fashioned notion these days) in December of that year.

Roosevelt used the image of American ideals of freedom as a symbol of the individual liberties being suppressed by the Fascist regime. (On a side note, “Fascist” has become a popular epithet with which some American political figures attempt to brand their political enemies these days. Most people who use it, or at least those who listen to them, apparently have no idea what the term actually means. Look it up.)

Rockwell, at the time the dominant star of American illustration, had a strong response to Roosevelt’s speech and two years later painted a series of four paintings depicting the four freedoms as scenes from American life.

He originally conceived series in 1942, and attempted to volunteer his services to the government agencies responsible for war propaganda, but was met with lack on interest. (“Propaganda“, by the way, is another term whose actual meaning is often lost in its buzzword connotations and popular interpretation. Again I suggest looking it up.)

Rockwell instead submitted the paintings to the Saturday Evening Post, for which he had been regularly painting covers, and their publication was met with great popular response and millions of requests for reprints.

The government eventually recognized the power of the images and used them on posters for the efforts to support the expense of the war with the sale of War Bonds (another quaint notion these days).

Rockwell himself reportedly struggled with the paintings, never entirely happy with them and concerned that they lacked sufficient power. He worked on them over a seven month period, during which he reportedly lost several pounds from the strain of working on them so intensely.

The public, however, loved them. They were reprinted on four million posters and were displayed in a touring exhibition that drew over a million visitors. They are now considered among Rockwell’s signature works, and were the subject of a book published in 1993 on the 50th anniversary of their original publication.

The four paintings are currently in the collection of the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, the director of which recently participated in the International Four Freedoms Award ceremonies in the Netherlands.

-

Q&A with architect Ole Scheeren | Architecture | Wallpaper* Magazine

Since leaving OMA earlier in the year, Ole Scheeren has scarcely touched the ground. To date, the German-born architect has found himself one of the key players shaping the architectural culture of the 21st century, and his involvement in the CCTV tower in Beijing, as project architect and leader (and founder) of OMA Asia, gave him a high profile platform from which to launch his own studio. Büro Ole Scheeren, officially announced last month, was co-founded with Eric Chang, also ex-OMA. Together, Scheeren and Chang have established an office of around 25 people, mostly in Beijing, with a Hong Kong outpost and plans for a satellite office in London as well.

See more work from Ole ScheerenFor a new studio, Büro-OS has an unparalleled amount of experience. Wallpaper* caught up with Scheeren on one of his regular trips to London, to discuss the new office and the initial projects that will help define how Büro-OS is perceived.

The final three projects overseen by Scheeren at OMA, The Scotts Tower and The Interlace building in Singapore and the MahaNakhon in Bangkok, are all concluded or on site; Büro-OS is effectively working with a clean sheet of paper.

Current projects include a 250m-tall mixed-use tower in Kuala Lumpur, a major new 800,000sq ft development in Chongqing, China, a new 2,000-seat theatre in Shanghai, as well as a small-scale studio and gallery for a Chinese artist in Beijing. Scheeren talks of an architecture specific to place, program and context, going far beyond star-struck iconism. We began by asking him how important context was to the studio’s work.

Ole Scheeren: What is important for me is that all projects inhabit a space between general or typographical relevance, and specific manifestations of their actual context. The tower in KL deals a lot with its location and how a skyscraper can connect to the activity of the city.

It’s a misassumption that there could ever be no context. No physical context at all. Perhaps no other architecture. But context goes beyond that: economical, political, psychological, climate, habits, standards, how people live, building regulations, a client’s needs and expectations. Every project is a negotiation between multiple factors. The question is at which point do you intervene and manipulate the factors?

In Singapore [with the Scott Tower] it was very explicit. We realised that the only way to unlock the mid-sized typology of an apartment tower is to go beyond the conventional tower archetype, which essentially only repeats the same plan vertically, while the role of the architect is reduced to decorating the façade. Instead we looked very carefully at the intersection between building regulations and the developers requirements, and focused on the core of the building, the non-sellable part. By manipulating that we found we could ‘dock’ more apartments into the tower on each floor and generate a new building configuration, with four suspended independent apartment towers floating in the air.

At The Interlace, the cores are also crucial – they penetrate the building volumes in three different rotations and allow for the hexagonal stacking of horizontal blocks instead of limiting the design to generic vertical towers. They form the superstructure, as well as the highly efficient and optimised circulation system. In architecture, you can only generate freedom by understanding a project and it’s specific context sufficiently well so that you can supersede what you’ve got.

W*: So are there any manifestos any more, or has ideology replaced them?

OS: I think currently there might be lack of both – of manifestos and ideology. What rather often seem to prevail are forms of opportunism and complacency. The question is how to develop a true position, how to embed your work in a context of meaning and relevance for the present and the future. Our ambition is to insert particular concepts into specific environments and to break open the static conditions of architectural production. We try to shift the focus away from the object-focused materiality of architecture and look at it as social constructs, as extensions of urban or personal realms. We don’t have pre-defined visions of architecture, and try to develop prototypes in close response to the actual project.

W* Does this then preclude you from working on vaguely-worded competition briefs? Do you need lots of information before you can start designing?

OS: Ideally yes, but not always. Context in this sense is something you partly create yourself. You’re not an innocent player in a wholly defined environment. The question is in which context do you want to insert yourself, and which aspects of it are you going to challenge?

I have started to look at a series of typologies, especially in Singapore. Very little prototyping is done in this area. There’s a status quo for this kind of project now – retail at base, maybe one ‘icon’ tower that legitimises everything else. It’s highly problematic.

W*: How do you go from conceptual to commercial? How do you find the clients?

OS: The choice of project and the choice of client is essential. The architect has to identify fertile situations. All the commercial clients I have worked with were in completely new territories with us. It’s about creating a very intense dialogue and personal engagement and you have to look at your own work from everyone else’s perspective.

Through the multiplicity of those understandings you can shift a radical idea into something that’s both plausible and exciting. You have a vision, and you have to be able to communicate this vision. But if you don’t create that moment of connect with a client, with all the economic and psychological realities involved, it simply doesn’t happen.

W*: Would you ever go into partnership with a like-minded developer?

OS: It’s a good question. I can see how establishing a methodology together could be beneficial. But on the other hand, the tension between architect and client – the multi-directionality inherent in this relationship – might ground a project in a far more radical position. The moment of surprise and challenge is very important, so while establishing such a partnership one needs to ensure this is not lost.

W*: How was your relationship with CCTV?

OS: CCTV is a very large and complex organisation. Most of the significant decisions were actually rather democratic, involving the board as well as lower-level employees and external advisors, all contributing their input to things that were at stake. Once things were decided they typically stood on a very broad basis of support. At the same time, there was a small group of people within the client organisation ultimately responsible for the project which was our true counterpart throughout the process. These people we were very close with, which might not be a surprise after eight years of collaboration.

W*: Is there still a place for the heroic in architecture?

OS: The notion of the hero is utterly uninteresting. Maybe, or hopefully, there’s a place for vision, but that’s also a problematic word. Perhaps we could call it ‘desire’ or ‘fantasy’. Although these also sometimes have heroic elements, that’s not the most interesting thing about them.

W*: What happens when you finish a building?

OS: You don’t build a building for the process. You build it for a future existence in a world that is out of your hands. It’s very exciting to think of buildings through these fictive scenarios, to play them through as a set of scenes.

W*: So there is no finished building?

OS: CCTV might be a blatant example: it will probably never be an entirely finished, stable entity that won’t change. At this scale even before the building has been fully occupied things will have changed, and the first part will have been adapted or converted. Architecture is an organism that keeps transforming through the life that it contains.

W*: How do you see Büro Ole Scheeren evolving?

OS: Since I stepped out [from OMA] quite a lot of work has been coming in, even before the new office was officially announced. The current projects are exciting, and the mix and scale is very important to me in defining the practice’s work on a broad and diverse basis, particularly at the beginning. But we are also looking into doing larger, more research-based projects, as well as exploring possibilities in city planning. Asia is a good place to be right now, and clients here particularly value our actual long-term presence and true involvement with the region. Nonetheless, it is important to me to maintain a connection to Europe and the rest of the world, and this is why we are preparing to undertake work in the West again and why we will open an office in London.

-

Rietveld’s Universe, Centraal Museum Utrecht, the Netherlands

This engrossing exhibition sets out to challenge some preconceptions. Its premise is that Gerrit Rietveld (1888-1964) is still primarily thought of for just two early designs, the Red Blue Chair (1918/23) and the Schröder House (1924), and that much of his long career is overlooked. Not that those two De Stijl icons have been admired unreservedly by all. Rem Koolhaas, for instance, has written that the house is ‘full of high purpose and sly intentions; full of colour, or at least of paint; full of abstract bells and sublimated whistles’.

Rietveld’s Universe almost refrains from giving star billing to the house and chair. Organised thematically rather than chronologically, with displays devoted to such subjects as ‘Liberating Space’ and ‘Simplicity and Experiment’, it absorbs them both into a larger narrative. We see the wide spectrum of Rietveld’s work, from urban design at one end to a continuing focus on furniture at the other. In-between come numerous building types, including academies, exhibition pavilions and private houses.

One dominant theme is Rietveld’s embrace of new materials and technologies. Exploring possibilities of prefabrication he came up with a ‘core house’, comprising a front door, hallway, stairwell and bathroom. He designed several different types of concrete block and was one of the first architects to realise a luminous ceiling. But he never had the opportunity to combine industrialised construction with social provision on the sort of scale he wished.

Exhibition designer Kinkorn has resisted the temptation of De Stijl’s primary colours and has instead chosen shades of grey for its refined and adroit installation. Visitors take a meandering route through the galleries, with many of the exhibits on trestle tables of varying height and images projected on screens overhead.Devoid of gimmicks, the show demands an audience that is willing to spend time examining drawings, material samples and Rietveld’s often quite rudimentary working models. There are none of the seductive colour photographs that graced 2G architecture magazine on Rietveld’s houses (November 2006) or Kaya Oku’s book The Architecture of Gerrit Rietveld (Toto, 2009).

Adding a little glamour and putting Rietveld in context are works by some of his international contemporaries. Models of Rietveld’s Van Slobbe House and Richard Neutra’s Lovell House, both built into a slope, sit side-by-side, with a drawing of Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House above them – an apposite ensemble. Less convincing is the juxtaposition of Rietveld’s thatched-roof Monsignor Verriet Institute,

on the island of Curaçao, with Le Corbusier’s Ronchamp chapel; Rietveld was hardly a practising expressionist.Published alongside the exhibition, the book Rietveld’s Universe (NAi Publishers, 2010) explores his career and critical reception in a dozen essays. It’s a valuable collection, which ranges from the cultural life of Rietveld’s hometown Utrecht to the way he detailed a corner, and out of it another Rietveld emerges: not just the standard bearer for De Stijl but a prescient environmentalist.

As long ago as 1958 Rietveld was saying: ‘Remember that the earth’s natural resources were not all designated for us… Learn to enjoy the wealth of restraint.’ In the book’s final essay, Netherlands Architecture Institute director Ole Bouman draws the obvious moral for the 21st century, stressing the purity and austerity of Rietveld’s conceptions: ‘He found meaning in the smallest space, fashioned something valuable from virtually nothing.’

So the book comes close to proposing Rietveld as a patron saint of sustainability, but it doesn’t quite canonise him. Yet instead of a new defining image of Rietveld’s work on the cover, what do we see? Yes, the Red Blue chair.

-

Tout Beethoven par le Philarmonique de Vienne

Peu d’orchestres ont une aura et un prestige comparable à ceux du Philharmonique de Vienne. C’est dû, bien sûr, à une sonorité unique, cultivée comme le plus précieux des jardins. Même si le recrutement s’est de plus en plus ouvert à des non Autrichiens (mais on ne compte encore que cinq femmes !), les membres ont tous reçu leur formation supérieure à Vienne, avec pour professeurs des membres du Philharmonique, élevés dans le style viennois. L’abondance de noms hongrois, tchèques ou balkaniques dans la liste des musiciens ferait même croire à une survivance de l’Empire austro-hongrois ! La facture instrumentale elle-même est spécifique : le hautbois viennois, avec son timbre couinant, ou le cor viennois, avec sa douceur de violoncelle, ne sont joués que dans cet orchestre.

Mais c’est surtout par son organisation et son mode de fonctionnement que les Wiener Philharmoniker sont tout à fait uniques. Les musiciens forment en réalité l’Orchestre de l’Opéra d’Etat de Vienne, dont ils sont salariés, avec pour mission de jouer tous les soirs dans ce prestigieux théâtre. Mais dès qu’ils quittent la fosse, ils se constituent en association autogérée, indépendante de l’Opéra, pour donner des concerts sous le nom d’Orchestre Philharmonique de Vienne. Un musicien recruté par l’Orchestre de l’Opéra reçoit en général le titre de Philharmoniker au bout de trois ans.

Pendant longtemps, le Philharmonique se contenta de donner dix concerts d’abonnement par saison, ainsi que le concert du Nouvel an, au Musikverein, et de jouer l’été au Festival de Salzbourg. Mais le succès aidant, l’orchestre est de plus en plus demandé, avec des résidences régulières à Paris, New York ou Tokyo, sans parler des enregistrements. Ils se partagent alors la recette, bien plus lucrative que leur salaire à l’Opéra : un problème que nouveau directeur, Dominique Meyer, a pris à bras le corps en obtenant enfin qu’ils soient mieux payés à l’Opéra, afin d’éviter qu’ils soient tentés de déserter la fosse.

L’organisation de travail de cet orchestre reste un tour de force, qui fait du responsable du planning la clé de voûte de l’édifice. Ces 149 musiciens doivent, en effet, assurer chaque soir une représentation lyrique, soit 300 levers de rideau sur 36 ouvrages lyriques et 7 ballets, tout en donnant 46 concerts à Vienne, 48 en tournée, et l’été 10 concerts et 20 représentations au Festival de Salzbourg !

Pour faire face à une telle charge de travail, la plus grande souplesse est de mise. Ainsi, lorsque l’orchestre est en tournée, l’Opéra programme des ouvrages ne réclamant pas un effectif trop important (plutôt Mozart et Rossini que Wagner et Strauss !). On trouve alors dans la fosse une équipe composée de Philharmoniker restés au pays, et de musiciens supplémentaires, recrutés notamment parmi des retraités, ou parmi des étudiants avancés, ce qui permet aussi de tester la relève. Il n’en reste pas moins que l’on a des souvenirs de soirées à l’Opéra de Vienne où l’on se rendait nettement compte qu’il y avait plus de remplaçants que de titulaires dans la fosse…

Obligés à la plus grande flexibilité, les musiciens viennois sont habitués à se relayer sans cesse, parfois dans le même ouvrage. Certains chefs, comme Claudio Abbado, ont cessé de les diriger faute d’avoir les mêmes instrumentistes de la première répétition à la dernière représentation : dans ce cas, ce sont les musiciens qui ont le dernier mot. C’est pourquoi le Philharmonique de Vienne n’a pas de directeur musical : les musiciens choisissent eux-mêmes leurs chefs, et élisent en leur sein un responsable de la billetterie, des médias, du planning. C’est la démocratie des rois.

-

Strada Tudor Arghezi

Superba locatia din postul anterior,insa trebuie sa revenim cu picioarele pe pamant. Spre exemplu, in Bucuresti.

Undeva pe strada TudorArghezi, in centru, detaliile arhitecturale sunt extraordinare… A doua imagine subliniaza lipsa de interes, lipsa de bun simt, lipsa de respect pentru valori, realitatea…

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

[Nikon D300; No Flash; Exposure time 1/400 sec; ISO 800; Exposure Compensation 0.0 Lens aperture F.5.6]

-

Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec by OMA

Dutch architects Office for Metropolitan Architecture have won a competition to design an extension to the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec in Canada. The winning design, announced today, is described as a “cascade of three overlapping boxes”. See all our stories about Rem Koolhaas/OMA in our special category. Here’s some info from OMA: – OMA WINS COMPETITION FOR MAJOR MUSEUM EXPANSION IN QUEBEC CITY New York, 31 March 2010 – The Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), has won the competition for a major expansion to the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec (MNBAQ). The 12,000m2 new building, a cascade of three overlapping boxes at the juncture of downtown Quebec City and the historic Battlefields Park, will be OMA’s first built project in Canada. The winner was announced today by MNBAQ President Pierre Lassonde and the Quebec Minister of Culture, Mme. Christine St-Pierre. The design, led by OMA partners Shohei Shigematsu and Rem Koolhaas in collaboration with associate Jason Long, was chosen unanimously from five submissions by internationally renowned architecture offices. OMA’s expansion of MNBAQ – linked underground with the museum’s three existing buildings – is located on Quebec’s main promenade, Grande-Allée, adjacent to St. Dominique Church. The design aims to integrate the building with the surrounding park and initiate new links with the city. Three stacked galleries of decreasing size – housing contemporary exhibitions (50m x 50m), the permanent contemporary collection (45m x 35m) and design / Inuit exhibits (42.5m x 25m) – ascend from the park towards the city, forming a dramatic cantilever towards the Grande-Allée and a 14m-high Grand Hall, welcoming the public into the new building. Shohei Shigematsu commented: “Our ambition is to create a dramatic new presence for the city, while maintaining a respectful, even stealthy approach to the museum’s neighbors and the existing museum. The resulting form of cascading gallery boxes enhances the museum experience by creating a clarity in circulation and curation while allowing abundant natural light into the galleries.” The project will be executed by OMA’s New York office in collaboration with Provencher Roy + Associés Architectes, with an anticipated completion date of fall 2013.